How does TidesDB work?

If you want to download the source of this document, you can find it here.

Want to watch a presentation instead?

Introduction

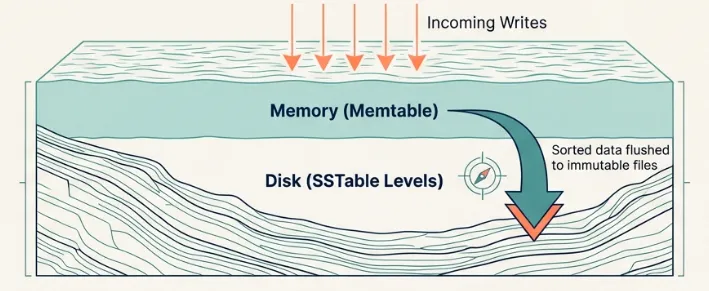

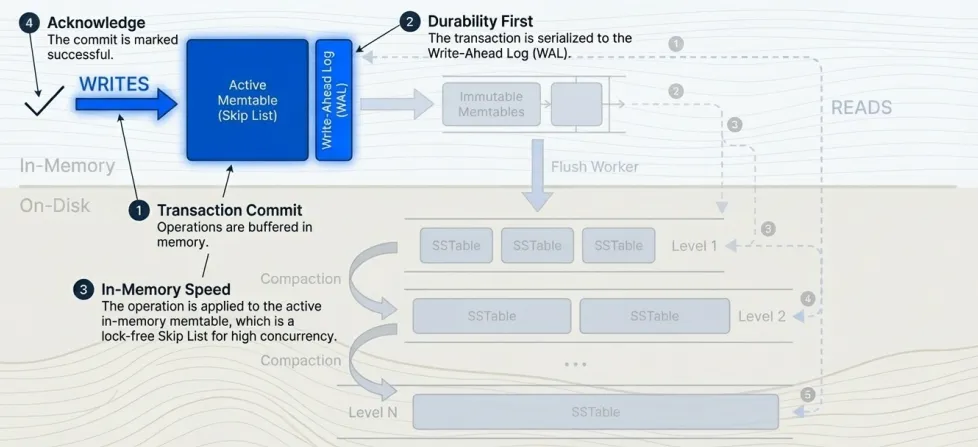

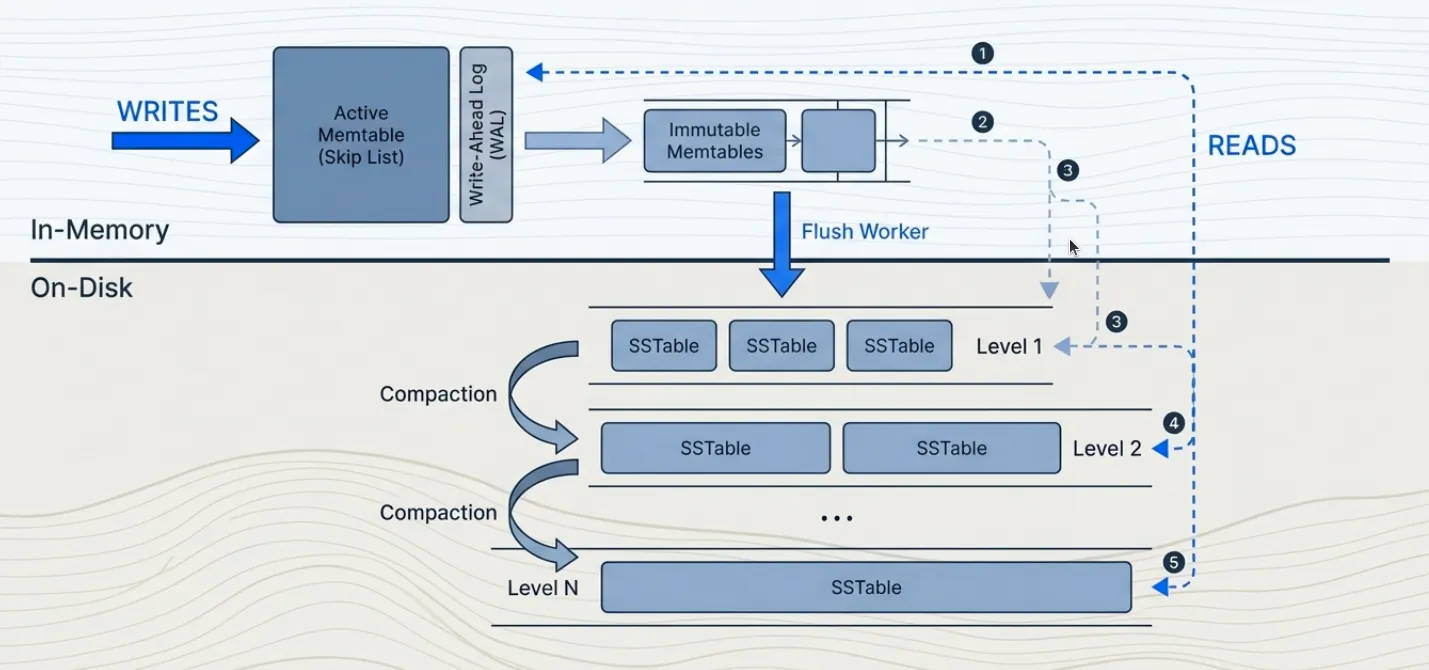

TidesDB is an embeddable key-value storage engine built on log-structured merge trees (LSM trees). LSM trees optimize for write-heavy workloads by batching writes in memory and flushing sorted runs to disk. This trades write amplification (data written multiple times during compaction) for improved write throughput and sequential I/O patterns. The fundamental tradeoff: writes are fast but reads must search multiple sorted files.

The system provides ACID transactions with five isolation levels and manages data through a hierarchy of sorted string tables (SSTables). Each level holds roughly N× more data than the previous level. Compaction merges SSTables from adjacent levels, discarding obsolete entries and reclaiming space.

Data flows from memory to disk in stages. Writes go to an in-memory skip list (chosen over AVL trees for easier lock-free potential and implementation) backed by a write-ahead log. When the skip list exceeds the set write buffer size, it becomes immutable and a background worker flushes it to disk as an SSTable. These tables accumulate in levels. Compaction merges tables from adjacent levels, maintaining the level size invariant.

Data Model

Column Families

The database organizes data into column families. Each column family is an independent key-value namespace with its own configuration, memtables, write-ahead logs, and disk levels.

This isolation allows different column families to use different compression algorithms, comparators, and tuning parameters within the same database instance.

A column family maintains:

- One active memtable for new writes

- A queue of immutable memtables awaiting flush to disk

- A write-ahead log paired with each memtable

- Up to 32 levels of sorted string tables on disk

- A manifest file tracking which SSTables belong to which levels

Sorted String Tables

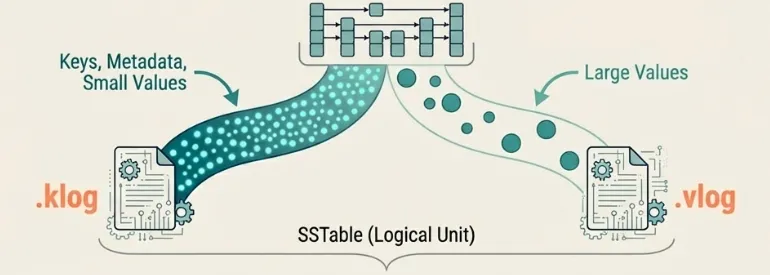

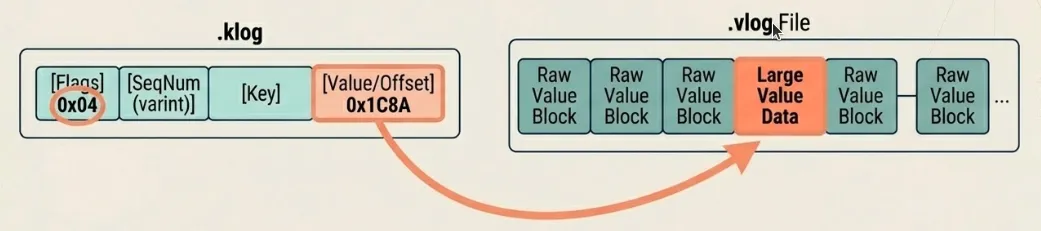

Each sorted string table (SSTable) consists of two files: a key log (.klog) and a value log (.vlog). The key log stores keys, metadata, and values smaller than the configured threshold (default 512 bytes). Values meeting or exceeding this threshold reside in the value log, with the key log storing only file offsets. This separation keeps the key log compact for efficient scanning while accommodating arbitrarily large values.

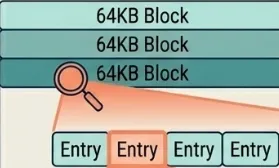

The key log uses a block-based format. Each block (fixed at 64KB) contains multiple entries serialized with variable-length integer encoding. Blocks compress independently using LZ4, LZ4-FAST, Zstd, or Snappy. The key log ends with three auxiliary structures: a block index for binary search, a bloom filter for negative lookups, and a metadata block with SSTable statistics.

B+tree Format (Optional)

Column families can optionally use a B+tree structure for the key log instead of the default block-based format. Enable this with use_btree=1 in the column family configuration. The B+tree stores all key-value entries exclusively in leaf nodes, with internal nodes containing only separator keys and child pointers for navigation. Leaf nodes are doubly-linked via prev_offset and next_offset pointers, enabling O(1) bidirectional traversal. The tree is immutable after construction - bulk-loaded from sorted memtable data during flush and never modified afterward.

During construction, the builder accumulates entries in a pending leaf until it reaches the target node size (default 64KB). When full, the leaf is serialized and written to disk. After all leaves are written, internal nodes are built level-by-level from separator keys extracted from each child’s first key. A backpatching pass then updates each leaf’s prev_offset and next_offset pointers to their final values. For compressed nodes, the leaf links are stored in a header before the compressed data, allowing the backpatch to update them without decompressing and recompressing the entire node.

Point lookups traverse from root to leaf using binary search at each internal node to select the correct child, then binary search within the leaf to locate the key. This yields O(log N) complexity where N is the number of nodes, compared to potentially scanning multiple 64KB blocks in the block-based format. Range scans use cursors that hold a reference to the current leaf node, advancing through entries before following the next_offset link to load the next leaf. Backward iteration follows prev_offset links similarly.

The B+tree format excels at point lookups and range scans with seeks. Point lookups benefit from O(log N) tree traversal versus potentially scanning multiple 64KB blocks in the block-based format. Range scans with seek() navigate directly to the target key position rather than scanning sequentially. Workloads with many small-to-medium SSTables see the most improvement, as each SSTable’s hot nodes remain cached independently. The block-based format remains preferable for sequential full-table scans and write-heavy workloads where B+tree metadata overhead during flush is less desirable.

When block_cache_size is configured, TidesDB creates a dedicated clock cache for B+tree nodes. Frequently accessed nodes remain in memory as fully deserialized structures, avoiding repeated disk reads and deserialization overhead. Cache keys combine the SSTable ID and node offset to ensure uniqueness across tables. On eviction, the callback frees the node’s memory via arena destruction. Cached nodes use arena allocation - all node memory (keys, values, metadata) is allocated from a single arena, enabling O(1) bulk deallocation when the node is evicted. When an SSTable is closed or deleted, all its cached nodes are invalidated by prefix scan to prevent stale references.

Large values meeting or exceeding the configured threshold (default 512 bytes) are written to the value log, with the leaf entry storing only the vlog offset. Nodes compress independently using LZ4, LZ4-FAST, Zstd, or Snappy. When bloom filters are enabled, they are checked before tree traversal - a negative result skips the B+tree lookup entirely, which is critical for LSM-trees where most SSTables won’t contain the requested key. SSTable metadata persists five additional fields for B+tree format: root offset, first leaf offset, last leaf offset, node count, and tree height, which are restored when reopening the SSTable.

Serialization optimizations · The B+tree uses several techniques to minimize serialized node size:

-

Varint encoding · Metadata fields (entry counts, key sizes, value sizes, vlog offsets) use LEB128-style variable-length integers. Small values (< 128) require only one byte; the full 64-bit range needs at most ten bytes. This typically saves 50-70% on metadata overhead compared to fixed-width integers.

-

Prefix compression · Keys within a leaf node share common prefixes with their predecessors. Each key stores only its suffix, with the prefix length encoded as a varint. During deserialization, keys are reconstructed by copying the prefix from the previous key. For sorted string keys with common prefixes (e.g., “user:1001”, “user:1002”), this achieves 60-80% key size reduction.

-

Key indirection table · Each leaf node contains a table of 2-byte offsets pointing to each key’s position within the node. This enables O(1) random access to any key during binary search without scanning through variable-length prefix-compressed keys sequentially.

-

Delta sequence encoding · Sequence numbers within a leaf are stored as signed deltas from a base sequence number (the minimum in the node). Since entries in a leaf typically have similar sequence numbers, deltas are small and compress well with varint encoding. TTL values use zigzag encoding for efficient signed integer representation.

-

Child offset deltas · Internal nodes store child offsets as cumulative signed deltas - each offset is encoded as the difference from the previous child’s offset, starting from a base offset (the first child). Since child nodes are typically written sequentially, deltas are small positive values that compress efficiently.

Leaf node format

[type:1][num_entries:varint][prev_offset:8][next_offset:8][key_offsets_table: num_entries × 2 bytes][base_seq:varint][entries: prefix_len:varint, suffix_len:varint, value_size:varint, vlog_offset:varint, seq_delta:signed_varint, ttl:signed_varint, flags:1][keys: prefix-compressed suffixes][values: inline values only]Internal node format

[type:1][num_keys:varint][base_offset:8][child_offset_deltas: signed_varint × (num_keys + 1)][key_sizes: varint × num_keys][separator_keys: raw key bytes]File Format

Each klog entry uses this format:

flags (1 byte)key_size (varint)value_size (varint)seq (varint)ttl (8 bytes, if HAS_TTL flag set)vlog_offset (varint, if HAS_VLOG flag set)key (key_size bytes)value (value_size bytes, if inline)The flags byte encodes tombstones (0x01), TTL presence (0x02), value log indirection (0x04), and delta sequence encoding (0x08). Variable-length integers save space: a value under 128 requires one byte, while the full 64-bit range needs at most ten bytes.

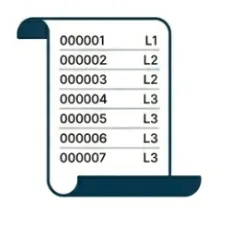

Write-ahead logs use the same format. Each memtable has its own WAL file, named by the SSTable ID it will become. Recovery reads these files in sequence order, deserializes entries into skip lists, and enqueues them for asynchronous flushing.

Transactions

Isolation Levels

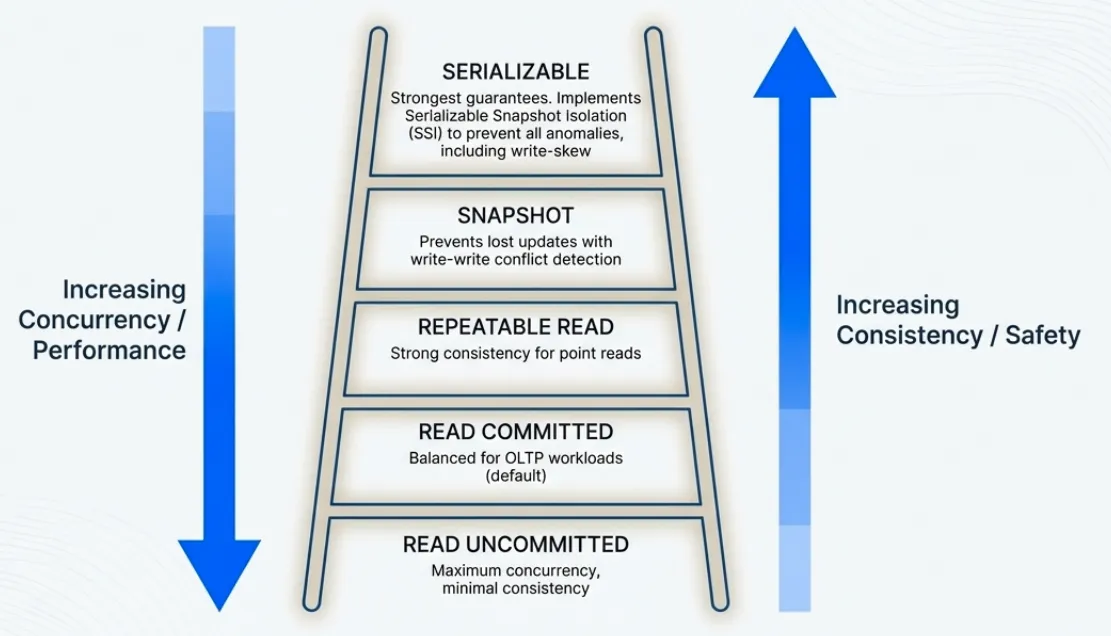

The system provides five isolation levels:

Read Uncommitted · sees all versions, including uncommitted ones. The snapshot sequence is set to UINT64_MAX.

Read Committed · performs no validation. Each read refreshes its snapshot to see the most recently committed version.

Repeatable Read · detects if any read key changed between read and commit time. The transaction tracks each key it reads along with the sequence number of the version it saw. At commit, it checks whether a newer version exists.

Snapshot Isolation · additionally checks for write-write conflicts. If another transaction committed a write to the same key after this transaction’s snapshot time, the commit aborts.

Serializable · implements serializable snapshot isolation (SSI). The system tracks read-write conflicts:

- Each transaction maintains a read set (arrays of CF pointers, keys, key sizes, sequence numbers)

- Creates a hash table (

tidesdb_read_set_hash_t) using xxHash for O(1) conflict detection when the read set exceedsTDB_TXN_READ_HASH_THRESHOLD(64 reads) - At commit, checks all concurrent transactions: if transaction T reads key K that another transaction T’ writes, sets

T.has_rw_conflict_out = 1andT'.has_rw_conflict_in = 1 - If both flags are set (transaction is a pivot in dangerous structure), aborts

This is simplified SSI - it detects pivot transactions but does not maintain a full precedence graph or perform cycle detection. False aborts are possible when non-pivot transactions have both flags set.

Multi-Version Concurrency Control

Each transaction receives a snapshot sequence number at begin time. For Read Uncommitted, this is UINT64_MAX (sees all versions). For Read Committed, it refreshes on each read. For Repeatable Read, Snapshot, and Serializable, the snapshot is global_seq - 1, capturing all transactions committed before this one started.

The snapshot sequence determines which versions the transaction sees: it reads the most recent version with sequence number less than or equal to its snapshot sequence.

At commit time, the system assigns a commit sequence number from a global atomic counter. It writes operations to the write-ahead log, applies them to the active memtable with the commit sequence, and marks the sequence as committed in a fixed-size circular buffer (defined by TDB_COMMIT_STATUS_BUFFER_SIZE, currently 65536 entries). The buffer wraps around: sequence N maps to slot N % 65536. When the buffer wraps, old entries are overwritten, so visibility checks for very old sequences may return incorrect results. In practice, this is acceptable because transactions with sequence numbers more than 65536 behind the current sequence are extremely rare. Readers skip versions whose sequence numbers are not yet marked committed.

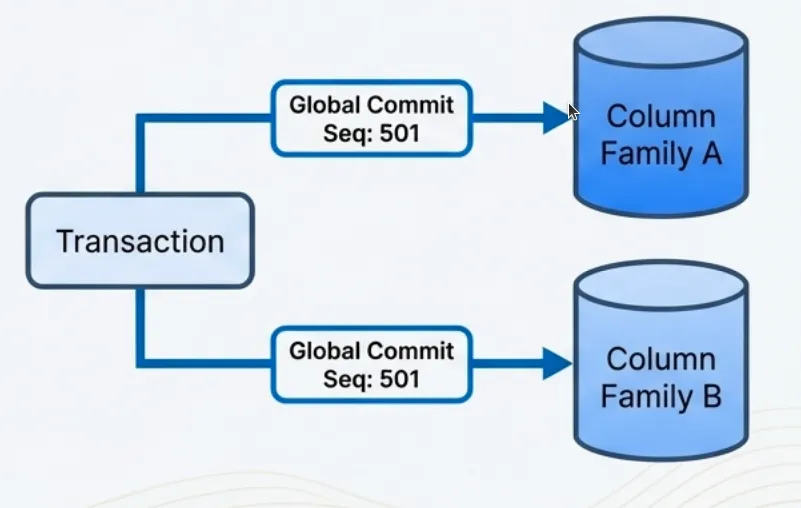

Multi-Column Family Transactions

TidesDB achieves multi-column-family transactions through an elegant design where the transaction structure maintains an array of all involved column families, and when you commit, it assigns operations across all these column families the same sequence number from a global atomic counter shared throughout the database. This shared sequence number serves as a lightweight coordination mechanism that ensures atomicity without the overhead of traditional two-phase commit protocols, as each column family’s write-ahead log records its operations with this same sequence number, effectively synchronizing the commit across all involved column families in a single atomic step.

Write Path

Transaction Commit

A transaction buffers operations in memory until commit. At commit time:

- The system validates according to isolation level

- It assigns a commit sequence number from the global counter

- It serializes operations to each column family’s write-ahead log

- It applies operations to the active memtable with the commit sequence

- It marks the commit sequence as committed in the status buffer

- It checks if any memtable exceeds its adaptive flush threshold

The transaction uses hash-based deduplication to apply only the final operation for each key. The hash table is created lazily when the transaction exceeds TDB_TXN_DEDUP_SKIP_THRESHOLD (8 operations) and is sized at TDB_TXN_DEDUP_HASH_MULTIPLIER (2×) the number of operations with a minimum of TDB_TXN_DEDUP_MIN_HASH_SIZE (64 slots). This is a fast non-cryptographic hash - collisions are possible but rare, and would cause the transaction to write both operations to the memtable (skip list handles duplicates correctly). This optimization reduces memtable size when a transaction modifies the same key multiple times.

Memtable Flush

When a memtable exceeds the flush threshold, the system atomically swaps in a new empty memtable and enqueues the old one for flushing. The swap takes one atomic store with a memory fence for visibility.

Adaptive flush threshold · The flush threshold is not a fixed value. At transaction commit, the system adjusts the threshold based on L0 immutable queue pressure to balance write batching against memory pressure. When the L0 queue is empty (idle), the threshold is 150% of write_buffer_size (50% headroom), allowing the memtable to accumulate more data before flushing for better batching. When 1 or more immutables are pending but below half the stall threshold (moderate), the threshold drops to 125% of write_buffer_size (25% headroom). When the L0 queue depth reaches 50% or more of l0_queue_stall_threshold (high pressure), the threshold equals write_buffer_size exactly (0% headroom), triggering an immediate flush. This adaptive mechanism reduces flush frequency during idle periods (improving write throughput) while ensuring rapid flushing under pressure (preventing memory buildup). With the default 64MB write buffer, the effective threshold ranges from 64MB under pressure to 96MB when idle.

A flush worker dequeues the immutable memtable and creates an SSTable. It iterates the skip list in sorted order, writing entries to 64KB blocks. Values meeting or exceeding the threshold (default 512 bytes) go to the value log; the key log stores only the file offset. The worker compresses each block optionally, writes the block index and bloom filter, and appends metadata. It then fsyncs both files, adds the SSTable to level 1, commits to the manifest, and deletes the write-ahead log.

The ordering is critical: fsync before manifest commit ensures the SSTable is durable before it becomes discoverable. Manifest commit before WAL deletion ensures crash recovery can find the data.

Crash scenarios · If the system crashes after fsync but before manifest commit, the SSTable exists on disk but is not discoverable - it becomes garbage and the reaper eventually deletes it. If it crashes after manifest commit but before WAL deletion, recovery finds both the SSTable and the WAL - it flushes the WAL again, creating a duplicate SSTable. The manifest deduplicates by SSTable ID.

Permissive validation · WAL files use block_manager_validate_last_block(bm, 0) (permissive mode). If the last block has invalid footer magic or incomplete data, the system truncates the file to the last valid block by walking backward through the file. This handles crashes during WAL writes. If no valid blocks exist, truncates to header only.

Strict validation · SSTables use block_manager_validate_last_block(bm, 1) (strict mode). Any corruption in the last block causes the SSTable to be rejected entirely. This reflects that SSTables are permanent and must be correct.

Write Backpressure and Flow Control

When writes arrive faster than flush workers can persist memtables to disk, immutable memtables accumulate in the flush queue. Without throttling, this causes unbounded memory growth. The system implements graduated backpressure based on the L0 immutable queue depth and L1 file count.

Each column family maintains a queue of immutable memtables awaiting flush. When the active memtable exceeds the adaptive flush threshold (see Memtable Flush above), it becomes immutable and enters this queue. A flush worker dequeues it asynchronously and writes it to an SSTable at level 1. The queue depth indicates how far behind the flush workers are.

Throttling thresholds · The system monitors two metrics:

- L0 queue depth · number of immutable memtables in the flush queue (configurable threshold, default 20)

- L1 file count · number of SSTables at level 1 (configurable trigger, default 4)

Graduated backpressure · The system applies increasing delays to transaction commits based on pressure, once per column family per commit:

Moderate pressure (50% of stall threshold or 3× L1 trigger) - Writes sleep for 0.5ms. This gently slows the write rate without significantly impacting throughput. At 50% of the default threshold (10 immutable memtables), writes experience minimal latency increase. The 0.5ms delay provides flush workers CPU time while remaining barely noticeable in multi-threaded workloads.

High pressure (80% of stall threshold or 4× L1 trigger) - Writes sleep for 2ms. This more aggressively reduces write throughput to give flush and compaction workers time to catch up. At 80% of the default threshold (16 immutable memtables), write latency increases noticeably but writes continue. The 4× escalation creates non-linear control response - since flush operations take ~120ms, the 2ms delay gives workers meaningful time to drain the queue.

Stall (≥100% of stall threshold) - Writes block completely until the queue drains below the threshold. The system checks queue depth every 10ms, waiting up to 10 seconds before timing out with an error. This prevents memory exhaustion when flush workers cannot keep pace. At the default threshold (20 immutable memtables), all writes stall until flush workers reduce the queue depth. The 10ms check interval balances responsiveness with syscall overhead.

Coordination with L1 · The backpressure mechanism considers both L0 queue depth and L1 file count. High L1 file count indicates compaction is falling behind, which will eventually slow flush operations (flush workers must wait for compaction to free space). By throttling writes based on L1 file count, the system prevents cascading backlog. L1 acts as a leading indicator - throttling occurs before L0 pressure becomes critical.

Memory protection · Each immutable memtable holds the full contents of a flushed memtable (default 64MB). With a stall threshold of 20, the system allows up to 1.28GB of immutable memtables plus the active memtable (64MB) before blocking writes. This bounds memory usage to roughly 1.34GB per column family under maximum write pressure, preventing out-of-memory conditions.

Immutable queue hard cap · To prevent truly unbounded memory growth from immutable accumulation, the flush path enforces a hard cap of 16 immutable memtables per column family. When the queue reaches this limit, the flush path blocks until the flush worker drains the queue below the cap. This complements the L0 stall threshold (which slows writes) by providing an absolute ceiling on immutable memory.

Global memory pressure · Per-column-family backpressure alone cannot prevent OOM when many column families accumulate memory simultaneously. The system maintains a global memory pressure level computed by the reaper thread every 100ms. The reaper sums all active memtables, immutable memtable estimates (using write_buffer_size as a conservative bound on each immutable’s data size), in-flight transaction memory (txn_memory_bytes), compaction temporary memory estimates, bloom filter bitsets, block index arrays, and cache memory across all column families, then computes the ratio against a resolved memory limit (configurable via max_memory_usage, default 50% of system RAM, minimum 5% of system RAM). Column family creation validates that write_buffer_size does not exceed the resolved memory limit. Cache sizes are validated at open time and clamped to 30% of the limit if they would exceed it. The pressure level is graduated: normal (< 60%), elevated (60-75%), high (75-90%), critical (≥ 90%). The write path reads this level with a single atomic load per commit - zero overhead at normal pressure. At elevated pressure, the adaptive flush threshold tightens to 100% of write_buffer_size (no headroom) and the write path proactively triggers a non-forced flush on the current column family if it is not already flushing, plus a 0.2ms yield to slow ingestion and prevent escalation (skipped if L0/L1 backpressure already applied a delay on this commit). At high pressure, the write path force-flushes the current column family and sleeps for 2ms (skipped if L0/L1 already delayed), while the reaper force-flushes the largest non-flushing active memtable. At critical pressure, the write path performs a self-help flush on the current column family (if not already flushing) and then blocks writes entirely until the reaper brings pressure below critical, timing out after 10 seconds with TDB_ERR_MEMORY_LIMIT. The reaper responds to critical pressure with a nuclear flush — force-flushing every column family that is not already flushing — plus aggressive compaction on the column family with the most SSTables. The is_flushing and is_compacting atomic flags are checked at every level to prevent redundant operations and ensure relief efforts target actionable column families. The L0 stall threshold scales dynamically in multi-CF deployments: the effective threshold is reduced when multiple column families share the memory budget, ensuring per-CF stall engages before global pressure reaches critical. An OS-level safety net polls get_available_memory() every ~5 seconds and overrides the pressure level to critical if real available memory drops below 5% of total system RAM, catching memory consumption from sources outside TidesDB’s tracking.

Worker coordination · The throttling mechanism assumes flush workers are making progress. If the queue depth remains at or above the stall threshold for 10 seconds (1000 iterations × 10ms), the system returns an error indicating the flush worker may be stuck. This typically indicates disk I/O failure, insufficient disk space, or a deadlock in the flush path.

Configuration interaction · Increasing write_buffer_size reduces flush frequency but increases memory usage during stalls. Increasing l0_queue_stall_threshold allows more memory usage but provides more buffering for bursty workloads. Increasing flush worker count reduces queue depth under sustained write load. Setting max_memory_usage caps the global memory envelope across all column families. The optimal configuration depends on write patterns, available memory, and disk throughput.

Design advantage · The graduated backpressure approach provides smooth degradation rather than traditional binary throttling (normal operation or complete stall), contributing to TidesDB’s sustained write performance advantage.

Read Path

Search Order

A read searches for a key in order:

- Active memtable

- Immutable memtables (newest to oldest)

- SSTables in level 1

- SSTables in level 2, then 3, and so on

The search stops at the first occurrence. Since newer data resides in earlier locations, this finds the most recent version.

SSTable Lookup

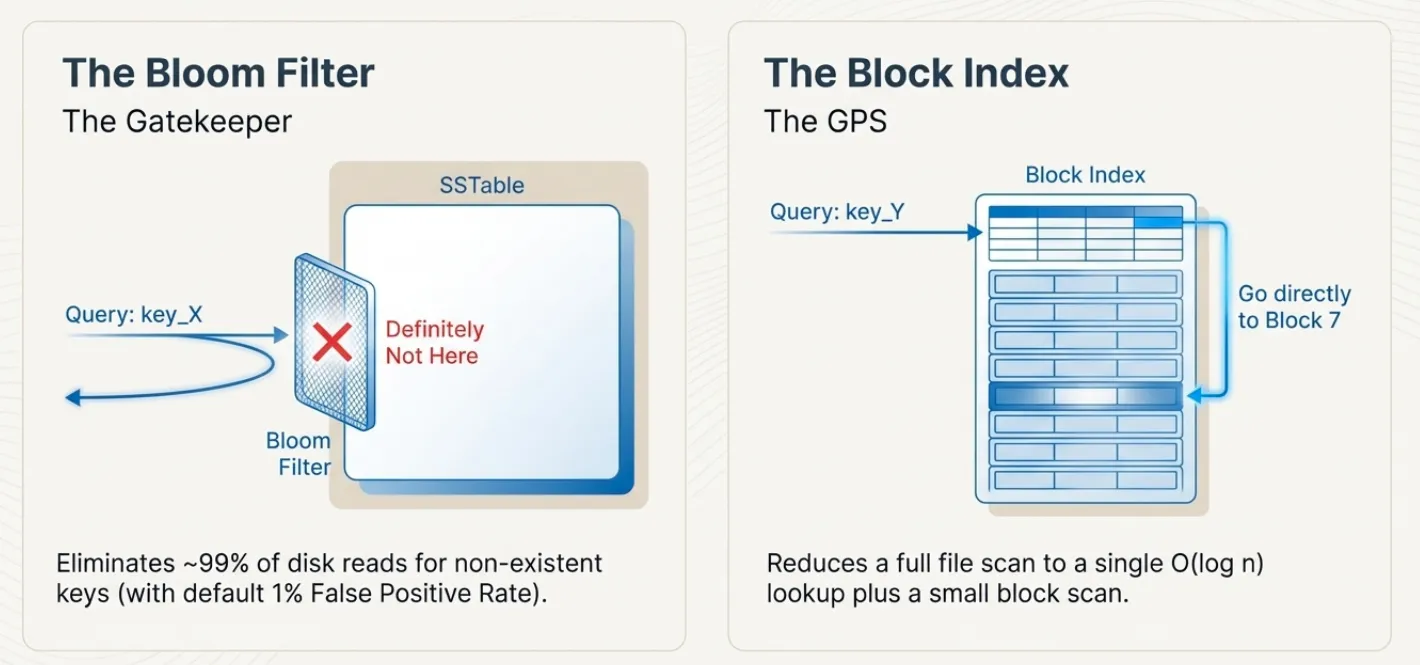

For each SSTable, the system:

- Checks min/max key bounds using the column family’s comparator

- If bloom filter exists (

enable_bloom_filter=1), checks it. If negative, the key is definitely absent. - If block index exists (

enable_block_indexes=1), finds which block might contain the key - Initializes a cursor at the block index hint (if available) or at the first block

- For each block:

- If block cache exists, generates cache key from column family name, SSTable ID, and block offset

- On cache hit, copies raw bytes from cache, decompresses if needed, and deserializes

- On cache miss, reads block from disk, decompresses if needed, deserializes, and caches the raw bytes

- Binary searches the block for the key

- If found and the entry has a vlog offset, reads the value from the value log

The bloom filter (default 1% FPR) and block index are optional optimizations configured per column family.

Bloom filter false positive cost · A false positive requires: (1) bloom filter check (memory access), (2) block index lookup (likely cache miss = disk read), (3) block read and deserialize (cache miss = disk read), (4) binary search block (memory). That’s 2 disk reads for a key that doesn’t exist. With 1% FPR and high query rate, this adds significant I/O.

The block cache uses a clock eviction policy with reference bits. Multiple readers share cached blocks without copying. The clock hand checks each entry’s ref_bit: if ref_bit == 0, the entry is evicted; if ref_bit > 0, it is cleared to 0 (second chance) and the hand moves on. Readers increment ref_bit when accessing an entry, protecting it from eviction during use.

Block Index

The block index enables fast key lookups by mapping key ranges to file offsets. Instead of scanning all blocks sequentially, the system uses binary search on the index to jump directly to the block that might contain the key.

Structure · The index stores three parallel arrays:

min_key_prefixes· First key prefix of each indexed block (configurable length, default 16 bytes)max_key_prefixes· Last key prefix of each indexed blockfile_positions· File offset where each block starts

Sparse Sampling · The index_sample_ratio (configurable via TDB_DEFAULT_INDEX_SAMPLE_RATIO, default 1) controls how many blocks to index. A ratio of 1 indexes every block; a ratio of 10 indexes every 10th block. Sparse indexing reduces memory usage at the cost of potentially scanning multiple blocks on lookup.

Prefix Compression · Keys are stored as fixed-length prefixes (default 16 bytes, configurable via block_index_prefix_len). Keys shorter than the prefix length are zero-padded. This trades precision for space - keys with identical prefixes may require scanning multiple blocks to disambiguate.

Binary Search Algorithm · compact_block_index_find_predecessor() finds the rightmost block where min_key <= search_key <= max_key:

- Create search key prefix (pad with zeros if shorter than prefix length)

- Early exit if search key < first block’s min key (return first block)

- Binary search for blocks where

min_key <= search_key <= max_key - Return the rightmost matching block (handles keys at block boundaries)

- If no exact match, return the last block where

min_key <= search_key

This ensures the search always starts from the correct block, avoiding false negatives when keys fall between indexed blocks.

Early Termination · When a block index successfully identifies the target block, the point read path enables early termination. If the key is not found in the indexed block, the search stops immediately rather than scanning subsequent blocks. Since blocks are sorted, the key cannot exist in later blocks if it wasn’t in the block the index pointed to. This optimization significantly reduces I/O for negative lookups and keys near block boundaries.

Serialization · The index serializes compactly using delta encoding for file positions (varints) and raw prefix bytes. Format: varint(count), varint(prefix_len), delta-encoded file positions, min key prefixes, max key prefixes. This achieves ~50% space savings compared to storing absolute positions.

Custom Comparators · The index supports pluggable comparator functions, allowing column families with custom key orderings (uint64, lexicographic, reverse, etc.) to use block indexes correctly.

Memory Usage · For an SSTable with 1000 blocks and default 16-byte prefixes: 32KB for prefixes + 8KB for positions = 40KB. With sparse sampling (ratio 10), this reduces to 4KB. The index is loaded into memory when an SSTable is opened and remains resident.

Usage in Seeks and Iteration · Block indexes are also used by iterator seek operations (tidesdb_iter_seek() and tidesdb_iter_seek_for_prev()). When seeking to a key:

- The block index finds the predecessor block using binary search

- The cursor jumps directly to that block position

- The iterator scans forward (or backward for

seek_for_prev) from there

This optimization is critical for range queries - without block indexes, seeking to a key in the middle of a large SSTable would require scanning all blocks from the beginning. With block indexes, the seek operation is O(log N) on the index plus O(M) scanning a few blocks, rather than O(N×M) scanning all blocks.

Block reuse fast path · When an SSTable source already has a deserialized block loaded and the seek target falls within that block’s key range (between the first and last key), the seek skips the expensive release, cache lookup, and deserialization cycle entirely and performs an in-place binary search on the existing block. This eliminates the dominant cost of repeated seeks to nearby keys. The fast path fires for both forward and backward seeks and handles edge cases where the target is before the current block (returns first entry) or after it (sequential advance to the next block via cursor_next, bypassing the block index binary search). For workloads with high seek locality, this reduces deserialization CPU from ~88% to ~8%. The sequential advance path is critical for monotonically advancing seeks (the common iteration pattern) where the next key is always in the next block.

Block boundary prefetch · When the iterator advances to the last entry in a klog block, it issues a posix_fadvise willneed hint on the next block’s file position so the OS begins reading it into the page cache before the iterator actually needs it. This hides I/O latency for sequential iteration across block boundaries.

Cached memtable sources · Iterator seek operations cache memtable sources (active memtable, immutable memtables, and transaction write buffer) on the iterator at creation time rather than recreating them on every seek call. This eliminates per-seek overhead of allocating source structs, initializing skip list cursors, traversing to the first entry, and creating initial key-value pairs. The cached sources are repositioned to the target key on each seek using the existing cursor seek operations. A pre-allocated temporary source array on the iterator avoids malloc/free of the source list on every seek as well. Combined with the SSTable source cache (which persists across seeks via cached_sources), this means the hot seek path performs zero memory allocations.

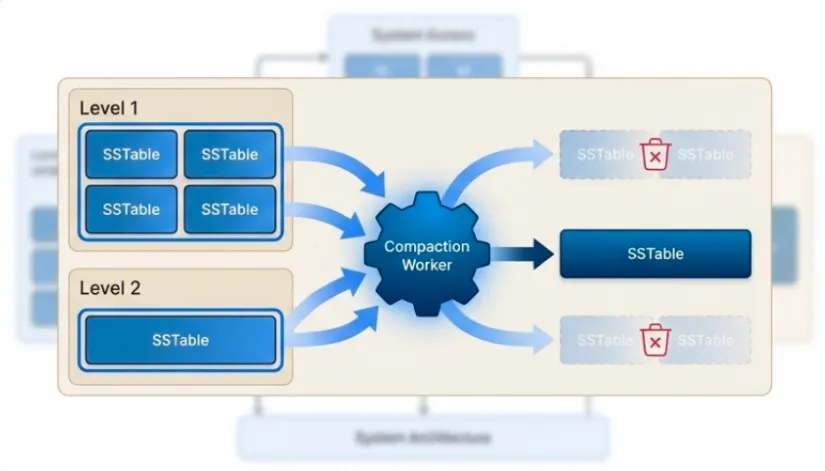

Compaction

Strategy

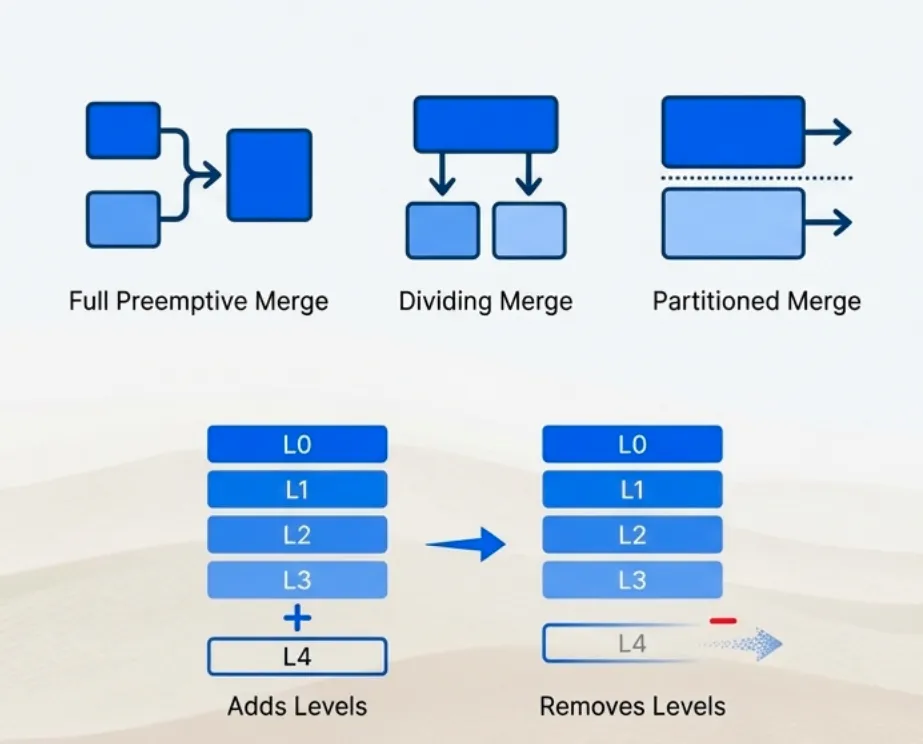

The strategy consists of three distinct policies based on the principles of the “Spooky” compaction algorithm described in academic literature, working in concert with Dynamic Capacity Adaptation (DCA) to maintain an efficient LSM-tree structure.

Overview

The primary goal of compaction in TidesDB is to reduce read amplification by merging multiple SSTable files, cleaning up obsolete data, and maintaining an efficient LSM-tree structure. TidesDB does not use traditional selectable policies (like Leveled or Tiered); instead, it employs three complementary merge strategies that are automatically selected based on the current state of the database.

The core logic resides in the tidesdb_trigger_compaction function, which acts as the central controller for the entire process.

Triggering Process

Compaction is triggered when specific thresholds are exceeded, indicating that the LSM-tree structure requires rebalancing.

Trigger Conditions

Compaction initiates under two conditions:

-

Level 1 SSTable accumulation · When Level 1 accumulates a threshold number of SSTables (configurable, default 4 files), the system recognizes that flushed memtables are piling up and need to be merged down into the LSM-tree hierarchy.

-

Level capacity exceeded · When any level’s total size exceeds its configured capacity, the system must merge data into the next level to maintain the level size invariant. Each level holds approximately N× more data than the previous level (configurable ratio, default 10×).

Calculating the Dividing Level

The algorithm calculates a dividing level (X) that serves as the primary compaction target. This is not a theoretical reference point but rather a concrete level in the LSM-tree computed using:

X = num_levels - 1 - dividing_level_offsetWhere dividing_level_offset is a configurable parameter (default 2) that controls compaction aggressiveness. A lower offset means more aggressive compaction (merging more frequently into higher levels), while a higher offset defers compaction work.

For example, with 7 active levels and the default offset of 2:

X = 7 - 1 - 2 = 4This means Level 4 serves as the primary merge destination.

Selecting the Merge Strategy

Based on the compaction trigger and the relationship between the affected level and the dividing level X, the algorithm selects one of three merge strategies:

-

If target level equals X · The system performs a dividing merge, merging all levels from 1 through X into level X+1. This is the default case when no level before X is overflowing.

-

If a level before X cannot accommodate the cumulative data · The system performs a full preemptive merge from level 1 to that target level. This handles cases where intermediate levels are filling up faster than expected.

-

After the initial merge, if level X is still full · The system performs a partitioned merge from level X to a computed target level z. This is a secondary cleanup phase that runs after the primary merge completes.

The Three Merge Modes

The compaction algorithm employs three distinct merge methods, each optimized for different scenarios within the LSM-tree lifecycle.

1. Full Preemptive Merge

This is the most straightforward merge operation. It combines all SSTables from two adjacent levels into the target level.

-

When it’s used

- When a level before the dividing level X cannot accommodate the cumulative data from levels 1 through that level.

- As a fallback mechanism by the other merge functions when they cannot determine partitioning boundaries (e.g., when there are no existing SSTables at the target level to use as partition guides).

-

What it does

- Takes a

start_levelandtarget_levelas input. - Opens all SSTables from both levels.

- Creates a min-heap containing merge sources from all SSTables.

- Iteratively pops the minimum key from the heap, writing surviving entries (non-tombstones, non-expired TTLs, keeping only the newest version by sequence number) to new SSTables at the target level.

- Fsyncs the new SSTables, commits them to the manifest, and marks old SSTables for deletion.

- Takes a

-

Characteristics

- Simple and effective for small-scale merges.

- Generates potentially large output files since it doesn’t partition the key space.

- Used when more sophisticated partitioning is not possible or necessary.

2. Dividing Merge

This is the standard, large-scale compaction method for maintaining the overall health of the LSM-tree. It is designed to periodically consolidate the upper levels of the tree into a deeper level.

-

When it’s used

- When the target level equals the dividing level X, which is the default case when no intermediate level is overflowing.

- This is the expected scenario during normal write-heavy workloads when Level 1 accumulates the threshold number of SSTables (default 4).

-

What it does

- Merges all levels from Level 1 through the dividing level X into level X+1.

- If X is the largest level in the database, the system first invokes Dynamic Capacity Adaptation (DCA) to add a new level before performing the merge. This ensures there’s always a destination level available.

- The merge is intelligent about partitioning. It examines level X+1 (the destination level) and extracts the minimum and maximum keys from each SSTable at that level. These key ranges serve as partition boundaries.

- The key space is divided into ranges based on these boundaries, and the merge is performed in chunks. Each chunk produces SSTables that cover only a single key range.

- This partitioning prevents the creation of monolithic SSTables and distributes data more evenly across the target level.

- If no partitioning boundaries can be determined (e.g., the target level is empty), the function falls back to calling

tidesdb_full_preemptive_merge.

-

Characteristics

- Handles large-scale data movement efficiently.

- Produces smaller, more manageable output files due to partitioning.

- Critical for maintaining read performance by preventing excessive file proliferation at upper levels.

3. Partitioned Merge

This is a specialized merge designed for secondary cleanup after the initial merge phase. It addresses scenarios where the dividing level X remains full after the primary merge operation.

-

When it’s used

- After the initial merge (dividing or full preemptive), when the dividing level X is still full (its size exceeds its capacity). This is a secondary cleanup phase that addresses remaining pressure at level X.

-

What it does

- Performs a merge on a specific range of levels (from level X to a computed target level z) rather than merging all the way from Level 1.

- Like

tidesdb_dividing_merge, it uses the largest level’s SSTable key ranges as partition boundaries. - It divides the key space and merges each partition independently, producing smaller output SSTables that each cover a single key range.

- This approach is more focused and less resource-intensive than a full dividing merge, allowing the system to relieve pressure in a specific area of the LSM-tree without triggering a full tree-wide compaction.

-

Characteristics

- Fast and targeted, addressing localized problems.

- Reduces the scope of compaction work compared to dividing merge.

- Helps prevent compaction from falling behind during bursty write patterns.

Dynamic Capacity Adaptation (DCA)

DCA is a separate mechanism from compaction. Whilst the three merge modes determine how to merge data, DCA determines when to add or remove levels from the LSM-tree structure and continuously recalibrates level capacities to match the actual data distribution.

The DCA Process

DCA is not a constantly running process. Instead, it is triggered automatically after operations that significantly change the structure or data distribution of the LSM-tree:

- After a compaction cycle completes · The

tidesdb_trigger_compactionfunction callstidesdb_apply_dcaat the end of its run. - After a level is removed · The

tidesdb_remove_levelfunction callstidesdb_apply_dcato rebalance the capacities of the remaining levels.

Capacity Recalculation Formula

The core of DCA is the tidesdb_apply_dca() function, which recalculates the capacity of all levels based on the actual size of the largest (bottom-most) level. The formula used is:

C_i = N_L / T^(L-i)Where:

C_i= the new calculated capacity for leveliN_L= the actual size in bytes of data in the largest levelL(the “ground truth” of how much data exists)T= the configured level size ratio between levels (default 10, meaning each level is 10× larger than the one above)L= the total number of active levels in the column familyi= the index of the current level being calculated

Execution steps

- Get the current number of active levels (

L). - Identify the largest level and measure its current total size (

N_L). - Iterate through all levels from Level 0 to Level

L-2(all levels except the largest). - For each level

i, apply the formula to calculate the new capacity (C_i), with a minimum floor ofwrite_buffer_size. - Update the

capacityproperty for that level with the newly calculated value.

This adaptive approach ensures that level capacities remain proportional to the real-world size of data at the bottom of the tree. As the database grows or shrinks, DCA automatically adjusts capacities to maintain optimal compaction timing - preventing both over-provisioned capacities (which cause high read amplification) and under-provisioned capacities (which cause excessive compaction and high write amplification).

Level Addition

DCA adds a new level when:

- The dividing merge attempts to merge into the largest level (X is the maximum level number).

- A level exceeds its capacity and needs a destination level that doesn’t yet exist.

Process

- The system creates a new empty level with capacity calculated using the formula:

write_buffer_size × T^(level_num-1), wherelevel_numis the new level’s number. - It atomically increments

num_active_levelsto reflect the new structure. - Normal compaction then moves data into this new level. The data is not moved during level addition itself to avoid complex data migration logic and potential key loss.

- After the compaction cycle completes,

tidesdb_apply_dca()is invoked to recalculate capacities for all levels based on actual data distribution.

Level Removal

DCA removes a level when:

- After compaction, the largest level becomes completely empty.

- The number of active levels exceeds the configured minimum (default 5 levels).

- The level was not just added in the current compaction cycle (newly added levels are intentionally empty).

- No pending flushes are queued and no SSTables exist at level 1 (prevents removing a level that incoming data is about to flow into).

Process

- The system verifies that

num_active_levels > min_levelsto prevent thrashing (repeatedly adding and removing levels). - It updates the new largest level’s capacity using the formula:

new_capacity = old_capacity / level_size_ratio. - It frees the empty level structure.

- It atomically decrements

num_active_levels. - It invokes

tidesdb_apply_dca()to rebalance all level capacities based on the new level count and the actual size of the new largest level.

Initialization

Column families start with a minimum number of pre-allocated levels (configurable via min_levels, default 5). During recovery:

- If the manifest indicates SSTables exist at level N where N > min_levels, the system initializes with N levels to accommodate the existing data.

- If SSTables exist only at levels below min_levels (e.g., only Levels 1-3), the system still initializes with min_levels (e.g., 5), leaving upper levels (4-5) empty.

- This floor prevents small databases from thrashing between 2-3 levels and guarantees predictable read performance by maintaining a minimum tree depth.

- After initialization,

tidesdb_apply_dca()is invoked to set appropriate capacities for all levels based on the actual data found during recovery.

The Merge Process

All three merge policies share a common merge execution path with slight variations:

Execution Steps

-

Open all source SSTables · The system opens the klog and vlog files for all SSTables involved in the merge (from both the source and target levels).

-

Create merge sources · For each SSTable, a merge source structure is created containing:

- The source type (SSTable or memtable, though memtables are typically only merged during flush).

- The current key-value pair being considered (

current_kv). - A cursor for iterating through the source (either a skip list cursor for memtables or a block manager cursor for SSTables).

-

Build a min-heap · The system constructs a min-heap (

tidesdb_merge_heap_t) with elements of typetidesdb_merge_source_t*. The heap orders sources by their current key using the column family’s configured comparator. -

Iterative merge · The system repeatedly pops the minimum element from the heap (the source with the smallest current key).

- It advances that source’s cursor to the next entry.

- It sifts the source back down into the heap based on its new current key.

-

Filtering and deduplication

- Tombstones · Entries marked as deleted are discarded and not written to the output.

- Expired TTLs · Entries whose time-to-live has expired are discarded.

- Duplicates · When multiple sources contain the same key, only the version with the highest sequence number (the newest version) is kept. Older versions are discarded.

-

Write to new SSTables

- Surviving entries are written to new SSTables at the target level.

- Data is written in blocks (fixed size 64KB).

- Values meeting or exceeding the configured threshold (default 512 bytes) are written to the value log (.vlog), while the key log (.klog) stores only the file offset.

- Values smaller than the threshold are stored inline in the key log.

- Blocks are optionally compressed using the column family’s configured compression algorithm (LZ4, LZ4-FAST, Zstd, or Snappy).

-

Finalize SSTables

- After all data is written, the system appends auxiliary structures to each key log: a block index for fast lookups, a bloom filter for negative lookups (if enabled), and a metadata block with SSTable statistics.

- The system fsyncs both the klog and vlog files to ensure durability.

-

Update manifest

- The new SSTables are committed to the manifest file, which tracks which SSTables belong to which levels.

- This operation is atomic - the manifest is written to a temporary file, fsynced, and atomically renamed over the original.

-

Delete old SSTables

- The old SSTables from the source and target levels are marked for deletion.

- The actual file deletion may be deferred by the reaper worker to avoid blocking the compaction worker.

Handling Corruption During Merge

If a source encounters corruption while its cursor is advancing:

- The

tidesdb_merge_heap_pop()function detects the corruption (via checksum failures in the block manager). - It returns the corrupted SSTable to the caller for deletion.

- The corrupted source is removed from the heap.

- The merge continues with the remaining sources.

- This ensures that compaction can complete even if one SSTable is damaged, allowing the system to recover by discarding the corrupted data.

Value Recompression

Large values (those meeting or exceeding the value log threshold) flow through compaction rather than being copied byte-for-byte:

- The system reads the value from the source value log.

- It recompresses the value according to the current column family configuration (which may differ from the original compression setting).

- It writes the recompressed value to the destination value log.

- This allows compression settings to evolve over time without requiring a full database rebuild.

TidesDB’s compaction is a sophisticated, multi-faceted algorithm that employs three distinct merge policies - full preemptive merge, dividing merge, and partitioned merge - each optimized for different scenarios within the LSM-tree lifecycle. These policies work in concert with Dynamic Capacity Adaptation (DCA) to automatically scale the tree structure up or down as data volume changes.

The system intelligently selects the appropriate merge strategy based on concrete triggers: when the target level equals the dividing level X, it performs a dividing merge; when a level before X cannot accommodate cumulative data, it performs a full preemptive merge; and after the initial merge, if level X remains full, it performs a partitioned merge as a secondary cleanup phase. The dividing level itself is calculated using a simple formula (num_levels - 1 - dividing_level_offset) rather than being inferred from complex bottleneck analysis.

This design allows TidesDB to handle a wide range of workloads efficiently, from steady-state writes to sudden bursts, while maintaining both read and write performance through intelligent data placement and compaction scheduling.

Recovery

On startup, the system scans each column family directory for write-ahead logs and SSTables. It reads the manifest file to determine which SSTables belong to which levels.

For each write-ahead log, ordered by sequence number:

- It opens the log file

- It validates the file, truncating partial writes at the end (permissive mode)

- It deserializes entries into a new skip list with the correct comparator

- It enqueues the skip list for asynchronous flushing

The manifest tracks the maximum sequence number across all SSTables. Recovery updates the global sequence counter to one past this maximum, ensuring new transactions receive higher sequence numbers than any existing data.

For SSTables, the system uses strict validation, rejecting any corruption. This reflects the different roles: logs are temporary and rebuilt on recovery; SSTables are permanent and must be correct.

Background Workers

Four worker pools handle asynchronous operations:

Flush workers (configurable, default 2 threads) dequeue immutable memtables and write them to SSTables. Multiple workers enable parallel flushing across column families.

Compaction workers (configurable, default 2 threads) merge SSTables across levels. Multiple workers enable parallel compaction of different level ranges.

Sync worker (1 thread) · periodically fsyncs write-ahead logs for column families configured with interval sync mode. It scans all column families, finds the minimum sync interval, sleeps for that duration, and fsyncs all WALs. This is only run if any of the column families during start up are configured with interval sync mode. If none are configured with interval sync mode, the sync worker is not started.

Mid-durability correctness · Column families configured with TDB_SYNC_INTERVAL propagate full sync to block managers during structural operations. When a memtable becomes immutable (rotation), the system escalates an fsync on the WAL to ensure durability before the memtable enters the flush queue. During sorted run creation and merge operations, block managers always receive explicit fsync calls regardless of the column family’s sync mode. This ensures correct durability guarantees for interval-based syncing while maintaining the performance benefits of batched syncs for normal writes.

Reaper worker (1 thread) performs three duties each cycle: global memory pressure computation, retired array reclamation, and unused file handle eviction. It sleeps for TDB_SSTABLE_REAPER_SLEEP_US (100ms) between cycles.

Global memory pressure · Each cycle, the reaper scans all column families to compute total memory usage: active memtable sizes (via atomic load), immutable queue estimates, bloom filter bitsets, block index arrays, and cache bytes. It divides this total by the resolved memory limit to produce a pressure level (normal, elevated, high, critical) stored atomically for the write path to consume. The reaper uses the is_flushing and is_compacting atomic flags to avoid redundant operations and target only actionable column families. When selecting a flush victim, it picks the column family with the largest active memtable that is not already flushing (mirroring the compaction victim selection which already filters by !is_compacting). At high pressure, the reaper force-flushes this single largest non-flushing column family. At critical pressure, the reaper performs a nuclear flush — force-flushing every column family that is not already flushing — to shed memory as fast as possible across the entire database. In both cases, the reaper also triggers aggressive compaction on the column family with the most SSTables (that is not already compacting), merging N SSTables into 1 to free N-1 bloom filters and block indexes, producing tighter replacements sized to the exact merged entry count.

Retired array reclamation · When flush or compaction swaps a level’s SSTable array (via atomic compare-and-swap), the old array cannot be freed immediately because concurrent readers may still be traversing it. Each level maintains an array_readers counter that readers increment before accessing the array and decrement after. Rather than spinning unboundedly waiting for readers to finish — which would block the flush or compaction worker and cause cascading stalls under mixed read-write workloads — the system attempts a brief spin (TDB_DEFERRED_FREE_SPIN_ATTEMPTS, default 64 iterations with cpu_pause) and, if readers are still active, pushes the retired pointer onto a lock-free deferred free list. The reaper sweeps this list every cycle: for each entry whose level has no active readers (array_readers == 0), it frees the retired array. Entries that still have active readers are re-enqueued for the next sweep. The lock-free list uses atomic compare-and-swap for push (producers are flush/compaction workers) and atomic exchange for bulk steal (consumer is the reaper). At shutdown, tidesdb_deferred_free_drain force-drains any remaining entries after the reaper thread has been joined.

File handle eviction · When the open SSTable count exceeds the limit (configurable via max_open_sstables, default 256 SSTables = 512 file descriptors), the reaper sorts open SSTables by last access time (updated atomically on each SSTable open, not on every read) and closes the oldest TDB_SSTABLE_REAPER_EVICT_RATIO (25%). With more SSTables than the limit, the reaper runs the eviction logic continuously, causing file descriptor thrashing.

Work Distribution

The database maintains two global work queues: one for flush operations, one for compaction operations. Each work item identifies the target column family. When a memtable exceeds its size threshold, the system enqueues a flush work item containing the column family pointer and immutable memtable. When a level exceeds capacity, it enqueues a compaction work item with the column family and level range.

Workers call queue_dequeue_wait() to block until work arrives. Multiple workers can process different column families simultaneously - worker 1 might flush column family A while worker 2 flushes column family B. Each column family uses atomic flags (is_flushing, is_compacting) with compare-and-swap to prevent concurrent operations on the same structure - only one flush can run per column family at a time, and only one compaction per column family at a time. The is_flushing flag is cleared in the flush worker after flush I/O completes, ensuring only one flush lifecycle (rotation + enqueue + I/O + cleanup) runs per column family at a time. This prevents cascading flush storms under write pressure. The public tidesdb_is_flushing() and tidesdb_is_compacting() functions check both the atomic flag and the respective work queue size, returning true if either indicates pending work.

Manual purge · The tidesdb_purge_cf() function provides a synchronous force-flush and aggressive compaction for a single column family. It waits for any in-progress flush to complete, force-flushes the active memtable, waits for flush I/O to finish, then triggers synchronous compaction inline (bypassing the compaction queue) and waits for any queued compaction to drain. The tidesdb_purge() function applies this to all column families and additionally drains both the global flush and compaction queues before returning. These are useful for manual maintenance, pre-backup preparation, or reclaiming space after bulk deletes.

Parallelism semantics

- Cross-CF parallelism · Multiple flush/compaction workers CAN process different column families in parallel

- Within-CF serialization · A single column family can only have one flush and one compaction running at any time

- No intra-CF memtable parallelism · Even if a CF has multiple immutable memtables queued, they are flushed sequentially (one at a time)

Thread pool sizing guidance

- Single column family · Set

num_flush_threads = 1andnum_compaction_threads = 1. Additional threads provide no benefit since only one operation per CF can run at a time - extra threads will simply wait idle. - Multiple column families · Set thread counts up to the number of column families. With N column families and M flush workers (where M ≤ N), flush latency is roughly N/M × flush_time. The global queue provides natural load balancing.

- Mixed workloads · If some CFs are write-heavy and others read-heavy, the thread pool automatically prioritizes work from active CFs.

Workers coordinate through thread-safe queues and atomic flags. The main thread enqueues work and returns immediately. Workers process work asynchronously, allowing high write throughput.

Error Handling

Functions return integer error codes. Zero indicates success; negative values indicate specific errors:

TDB_ERR_MEMORY(-1): allocation failureTDB_ERR_INVALID_ARGS(-2): invalid parametersTDB_ERR_NOT_FOUND(-3): key not foundTDB_ERR_IO(-4): I/O errorTDB_ERR_CORRUPTION(-5): data corruption detectedTDB_ERR_EXISTS(-6): resource already existsTDB_ERR_CONFLICT(-7): transaction conflictTDB_ERR_TOO_LARGE(-8): key or value too largeTDB_ERR_MEMORY_LIMIT(-9): memory limit exceededTDB_ERR_INVALID_DB(-10): invalid database handleTDB_ERR_UNKNOWN(-11): unknown errorTDB_ERR_LOCKED(-12): database is locked by another process

More status codes can be seen in the C reference section.

The system distinguishes transient errors (disk space, memory) from permanent errors (corruption, invalid arguments). Critical operations use fsync for durability. All disk reads validate checksums at the block manager level. At a higher level the system utilizes magic numbers to detect corruption at the SSTable level.

Error scenarios

-

Disk full during flush · Flush fails, memtable remains in immutable queue. Writes continue to active memtable. When active memtable fills, writes stall (no more memtable swaps possible). System logs error but does not fail writes until memory exhausted.

-

Corruption during read · Returns

TDB_ERR_CORRUPTIONto caller. Does not mark SSTable as bad - subsequent reads may succeed if corruption is localized to one block. -

Corruption during compaction ·

tidesdb_merge_heap_pop()detects corruption when advancing a source, returns the corrupted SSTable. Compaction marks it for deletion and continues with remaining sources. -

Memory allocation failure during compaction · Compaction aborts, returns

TDB_ERR_MEMORY. Old SSTables remain intact. Compaction retries on next trigger. -

Comparator changes between restarts · Keys will be in wrong order within SSTables. Binary search will miss existing keys (returns NOT_FOUND for keys that exist). Iterators will return keys out of order. Compaction will produce incorrectly sorted output. The system does not detect comparator changes - this is a configuration error that corrupts the logical structure without corrupting the physical data.

-

Bloom filter false positives · Cause 2 unnecessary disk reads (block index + block) but no errors.

Design Rationale

Block Size

Blocks balance compression efficiency and random access granularity. Larger blocks compress better (more context for LZ4/Zstd) but require reading more data for point lookups. Smaller blocks reduce read amplification but compress poorly and increase block index size. The fixed 64KB block size matches common SSD page sizes and provides reasonable compression ratios (typically 2-3× for text data). The tradeoff: a point lookup reads 64KB even for a 100-byte value.

Level Size Ratio

Each level holds N× more data than the previous level. This determines write amplification. Lower ratios (5×) reduce write amp but increase levels (worse reads). Higher ratios (20×) reduce levels but increase write amp. The ratio is configurable per column family (default 10×).

Write amplification · In leveled compaction, each entry gets rewritten once per level it passes through. With ratio R and L levels, average write amplification is approximately R × L / 2 (not R × L) because data at shallow levels gets rewritten more than data at deep levels. For a 1TB database with default 64MB L1 and ratio 10: log₁₀(1TB/64MB) ≈ 7 levels, so ~35× average write amplification (not 70×). Actual write amp depends on workload - updates to existing keys have lower write amp than pure inserts.

Read amplification · Worst case reads one SSTable per level. With 7 levels, that’s 7 disk reads without bloom filters. Bloom filters (1% FPR) reduce this: expected reads ≈ 1 + 7×0.01 = 1.07 for absent keys. This is an approximation valid for small FPR (probability of no false positives across all levels ≈ 0.99^7 ≈ 0.93). For present keys, bloom filters don’t help - still need to read the actual block.

Value Log Threshold

Values meeting or exceeding the configured threshold (default 512 bytes) go to the value log. This keeps the key log compact for efficient scanning. The threshold balances two costs: small thresholds cause many value log lookups (extra disk seeks); large thresholds bloat the key log (more data to scan during iteration). The default 512 bytes is a heuristic - it’s roughly the size where the indirection cost (reading vlog offset, seeking to vlog, reading value) becomes cheaper than scanning a large inline value during iteration.

Bloom Filter FPR

The default 1% false positive rate balances memory usage and effectiveness. Lower FPR (0.1%) requires 10× more bits per key but only reduces false positives by 10×. Higher FPR (5%) saves memory but causes more unnecessary disk reads. At 1% FPR, a bloom filter uses roughly 10 bits per key. For 1M keys, that’s 1.25MB - small enough to keep in memory. The FPR is configurable per column family.

Memtable Size

Larger memtables reduce flush frequency but increase recovery time and memory usage. Smaller memtables flush more often (more SSTables, more compaction) but recover faster. The default size is 64MB, which holds roughly 1M small key-value pairs and flushes every few seconds under moderate write load.

Configuration interaction · Increasing memtable size to 128MB reduces flush frequency by 2× but also increases L0->L1 write amplification because each flush produces a larger SSTable that takes longer to merge. The optimal size depends on write rate and acceptable recovery time.

Worker Thread Counts

The default configuration uses 2 flush workers and 2 compaction workers to enable parallelism across column families while limiting resource usage. More threads help with multiple active column families but increase memory (each worker buffers 64KB blocks during merge) and file descriptor usage (2 FDs per SSTable being read/written). The counts are configurable.

Tradeoff · With N column families and 2 flush workers, flush latency is roughly N/2 × flush_time. Increasing to 4 workers halves latency but doubles memory usage during concurrent flushes.

Disk contention · On HDDs, multiple concurrent compaction workers cause head seeks, destroying throughput. On NVMe SSDs with high parallelism, multiple workers improve throughput. Choose worker counts based on storage device characteristics: 1-2 workers for HDD, 4-8 for NVMe.

Operational Considerations

Concurrency and Process Safety

TidesDB database instances are multi-thread safe and single-process exclusive.

Multiprocess safety

Only one process can open a database directory at a time. The system acquires an exclusive file lock on a lock file named LOCK within the database directory during tidesdb_open(). The lock is non-blocking - if another process holds the lock, tidesdb_open() returns TDB_ERR_LOCKED immediately rather than waiting. The implementation uses platform-specific locking primitives: fcntl() F_SETLK on macOS/BSD (chosen over flock() because fcntl locks are not inherited across fork(), preventing child processes from inheriting the parent’s lock), flock() on older systems without F_OFD_SETLK, and F_OFD_SETLK on Linux 3.15+ for per-file-descriptor semantics. On macOS/BSD, the system additionally writes the owning process’s PID to the lock file after acquiring the lock, enabling detection of same-process double-open attempts (since fcntl allows the same process to re-acquire its own lock). The lock is released and the PID cleared during tidesdb_close(). On Windows, the system uses LockFileEx() with LOCKFILE_EXCLUSIVE_LOCK | LOCKFILE_FAIL_IMMEDIATELY for equivalent non-blocking exclusive locking. The lock acquisition includes retry logic (default 3 retries) specifically for EINTR errors, which occur when a signal interrupts the locking syscall - this ensures transient signal interruptions don’t cause spurious lock failures.

Memory Footprint

Per column family:

- Active memtable · configurable (default 64MB)

- Immutable memtables · memtable_size × queue depth (typically 1-2)

- Block cache · shared across all column families (configurable, default 64MB total)

- Bloom filters · ~10 bits per key across all SSTables (depends on FPR)

- Block indexes · ~32 bytes per block across all SSTables

For a column family with 10M keys across 100 SSTables using defaults: ~12MB bloom filters, ~2MB block indexes, 128MB memtables. Total: ~150MB plus block cache share.

Global memory limit · The max_memory_usage configuration (default 0 = auto) sets an upper bound on total tracked memory across all column families. When set to 0, the system resolves this to 50% of total system RAM at startup, with a minimum floor of 5% of total RAM. The reaper thread monitors the aggregate of memtables, caches, bloom filters, and block indexes against this limit, applying graduated pressure to the write path and triggering force-flushes and aggressive compaction when usage exceeds thresholds. This prevents OOM in multi-column-family deployments where per-CF limits alone cannot bound aggregate memory consumption.

Compaction Lag

Writes can outpace compaction if the write rate exceeds the compaction throughput. The system applies backpressure: when L0 exceeds 20 immutable memtables (configurable via l0_queue_stall_threshold), writes stall until flush workers catch up. This prevents unbounded memory growth but can cause write latency spikes.

Disk Space

SSTables are immutable - space isn’t reclaimed until compaction completes and old SSTables are deleted. Worst case: during compaction, both input and output SSTables exist simultaneously. For a level with 1GB of data, compaction temporarily requires 2GB. The system checks available disk space before starting compaction.

File Descriptor Usage

Each SSTable uses 2 file descriptors (klog and vlog). When the number of SSTables exceeds the open file limit (default 256), the reaper closes the least recently used files. With many SSTables, this can cause file descriptor thrashing as files are repeatedly opened and closed. 256 files is equivalent to 512 open file descriptors.

Internal Components

TidesDB’s internal components are designed as reusable, well-tested modules with clean interfaces. Each component solves a specific problem and integrates with the core LSM tree implementation through clearly defined APIs.

Block Manager

The block manager provides a lock-free, append-only file abstraction with atomic reference counting and checksumming. Each file begins with an 8-byte header (3-byte magic “TDB”, 1-byte version, 4-byte padding). Blocks consist of a header (4-byte size, 4-byte xxHash32 checksum), data, and footer (4-byte size duplicate, 4-byte magic “BTDB”) for fast backward validation.

Lock-free concurrency · Writers use pread/pwrite for position-independent I/O, allowing concurrent reads and writes without locks. Block writes use pwritev to combine the header, data, and footer into a single scatter-gather syscall (3 syscalls → 1), improving sequential and parallel write throughput by 2-2.5×. These POSIX functions are abstracted through compat.h for cross-platform support (Windows uses ReadFile/WriteFile with OVERLAPPED structures). The file size is tracked atomically in memory to avoid syscalls. Blocks use atomic reference counting - callers must call block_manager_block_release() when done, and blocks free when refcount reaches zero. Durability operations use fdatasync (also abstracted via compat.h).

Read path optimizations · Block reads use two pread syscalls: one for the 8-byte header (size + checksum) and one for the data payload directly into the final allocation, avoiding intermediate buffer copies. The fused block_manager_cursor_read_and_advance() operation combines read and cursor advance into a single call, using the block size from the just-read block to compute the next position without a redundant pread. Cursors also cache block sizes from previous operations, allowing cursor_read_partial() to skip the size lookup when the cache is valid. These optimizations reduce syscall overhead on the hot read path.

Cursor abstraction · Block manager cursors enable sequential and random access. Cursors maintain current position and can move forward, backward, or jump to specific offsets. The cursor_read_partial() operation reads only the first N bytes of a block, useful for reading headers without loading large values.

Validation modes · The system supports strict (reject any corruption) and permissive (truncate to last valid block) validation. WAL files use permissive mode to handle crashes during writes. SSTable files use strict mode since they must be correct. Validation walks backward from the file end, checking footer magic numbers.

Integration · TidesDB uses block managers for all persistent storage - WAL files, klog files, and vlog files. The atomic offset allocation enables concurrent flush and compaction workers to write to different files simultaneously. The reference counting prevents use-after-free when multiple readers access the same SSTable.

Bloom Filter

Sparse serialization · The filter serializes using varint encoding for headers and sparse encoding for the bitset - it stores only non-zero words with their indices. This achieves 70-90% space savings for low fill rates (< 50%). The serialization format: varint(m), varint(h), varint(non_zero_count), then pairs of varint(index) and uint64_t(word).

Hash function · Uses a simple multiplicative hash with different seeds for each of the h hash functions. Each hash sets one bit in the bitset using bitset[hash % m / 64] |= (1ULL << (hash % 64)).

Integration · TidesDB creates one bloom filter per SSTable during flush and merges, adding all keys. The filter is serialized and written to the klog file after data blocks. During reads, the system checks the bloom filter before consulting the block index. With 1% FPR, this eliminates 99% of disk reads for absent keys. The filter is loaded into memory when an SSTable is opened and remains resident.

Buffer

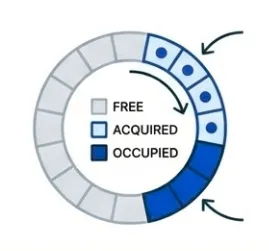

The buffer provides a lock-free slot allocator with atomic state machines and generation counters for ABA prevention. Each slot has four states: FREE (0), ACQUIRED (1), OCCUPIED (2), RELEASING (3). State transitions use atomic compare-and-swap operations.

Lock-free acquire · buffer_acquire() scans from a hint index (atomically incremented) to find a FREE slot, atomically transitions it to ACQUIRED, stores data, then transitions to OCCUPIED. If no slots are available, it retries with exponential backoff. The hint index reduces contention by spreading acquire attempts across the buffer.

Generation counters · Each slot maintains a generation counter incremented on release. This prevents ABA problems where a slot is released and reacquired between two operations. Callers can validate (slot_id, generation) pairs to ensure they’re still referencing the same allocation.

Eviction callbacks · The buffer supports optional eviction callbacks invoked when slots are released. This enables custom cleanup logic without requiring callers to track allocations.

Integration · TidesDB uses buffers for tracking active transactions in each column family (active_txn_buffer, configurable, default 64K slots). During serializable isolation, the system needs to detect conflicts between concurrent transactions. The buffer stores transaction entries that can be quickly scanned for conflict detection. The eviction callback (txn_entry_evict) frees transaction metadata when slots are released. The lock-free design allows concurrent transaction begins without blocking.

Clock Cache

The clock cache implements a partitioned, lock-free cache with hybrid hash table + CLOCK eviction. Each partition contains a circular array of slots for CLOCK and a separate hash index for O(1) lookups. The hash index uses XXH3_64bits hashing with linear probing and a maximum probe distance of 128.

Partitioning · The cache divides into N partitions (default: 4 per CPU core, up to 512). Each partition has independent CLOCK hand and hash index. Keys are hashed to partitions using hash(key) & partition_mask. This reduces contention - with 64 partitions and 16 threads, average contention is 16/64 = 0.25 threads per partition.

NUMA-aware partition routing · On multi-CCX processors (AMD Threadripper, EPYC), the cache detects L3 cache topology by reading /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu*/cache/index3/id on Linux. CPUs sharing an L3 cache are grouped together, and partitions are divided equally among groups. When routing a key, the system calls sched_getcpu() (a fast vDSO call, ~5ns) to determine which L3 group the calling thread belongs to, then selects a partition local to that group. The group ID is cached in thread-local storage so subsequent lookups avoid the syscall. On monolithic dies (single L3 group) or non-Linux platforms, this reduces to simple hash & partition_mask. On Windows, GetCurrentProcessorNumber() provides the CPU ID.

Cache-line-aligned layout · The partition struct is carefully laid out to prevent false sharing. Cache line 0 holds read-only fields (slots pointer, hash index, masks) that are immutable after initialization. Cache line 1 holds eviction-path atomics (clock_hand, occupied_count, bytes_used) accessed only by writers. Cache line 2 holds per-partition hit/miss counters accessed only by readers. Statistics are aggregated from per-partition counters on demand, avoiding contention on global counters.

Lock-free operations · Entries use atomic state machines (EMPTY, WRITING, VALID, DELETING). The ref_bit field encodes two things: the LSB is the CLOCK recently-used flag, and the upper bits are an active reader count (incremented by 2 per reader). Get operations are fully lock-free: hash to partition, prefetch the first hash index entry, probe the hash index for a matching slot while prefetching both the slot data and next hash index entry simultaneously to overlap memory latency, atomically increment the reader count, re-validate state, compare keys, and return the pointer. If hash index probing fails (rare overflow), a capped linear fallback scans up to 128 slots. Put operations claim a slot via the CLOCK eviction sweep, which starts from a thread-local position to reduce contention on the global clock_hand. The sweep prefetches 2 entries ahead during scanning. Key and payload are stored in a single allocation (8-byte aligned) to halve malloc calls and improve data locality.

Eviction · The CLOCK hand gives entries with the recently-used bit set a second chance by clearing the bit and moving on; entries with the bit clear and no active readers are evicted. Eviction checks active readers twice - once before clearing pointers, and again after clearing but before freeing, to handle races where a reader acquired a reference between the two checks. If readers appeared, the eviction is reverted (pointers restored, state reset to VALID). Partitions trigger proactive eviction when occupancy exceeds 85%.

Zero-copy reads · clock_cache_get_zero_copy() returns a pointer to cached data without copying. The reader count in the upper bits of ref_bit protects the entry from eviction while in use. Callers must call clock_cache_release() to decrement the reader count when done.